|

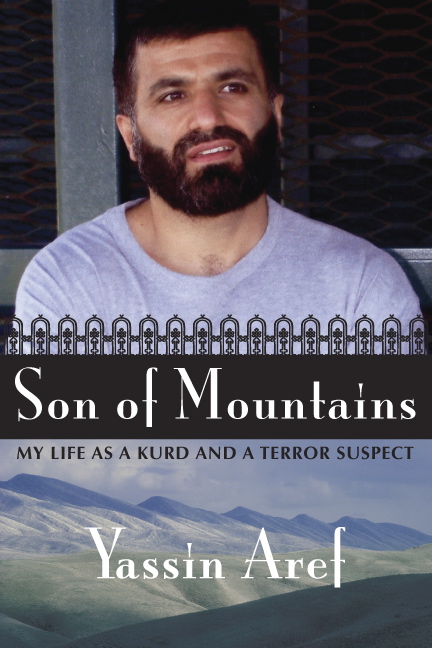

Son of Mountains

|

Son of Mountains

My Life as a Kurd and a Terror Suspect

by Yassin Aref

There are a few copies of Son of Mountains remaining. There are only a few copies of Son of Mountains remaining at two online outlets. If you would like a copy of the book, you can order it through the AET Book Club at:

http://www.middleeastbooks.com/aetbookclub/nonfiction/aref-sonofmountains.htmlor through the publisher, The Troy Book Makers, please click here.

The price is $27. All proceeds go to the Aref Children's Fund, to benefit Yassin's four children.

Read about book events:

Spencertown Festival of Books, September 7, 2008

Save the Pine Bush Book Signing, May 14, 2008

Publication date: March 10, 2008

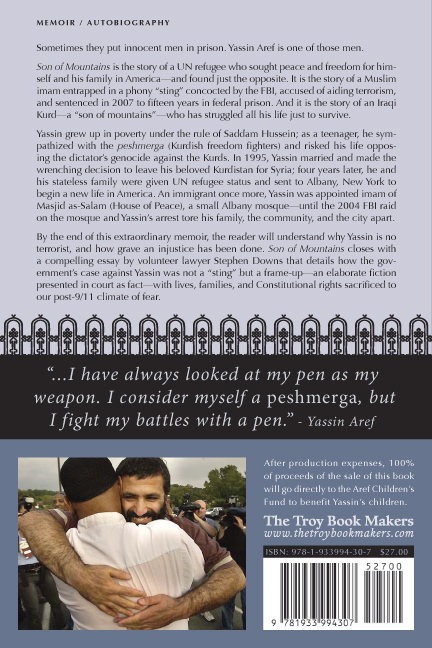

Softcover, photographs, Approximately 540 pages

544 pages, paperback, photographs and photo insert

ISBN: 978-1-933994-30-7

First edition of 750 copies, printed by The Troy Book Makers

Price: $27.00After production expenses, all proceeds from sales will go to the Aref Children’s Fund, to benefit the author’s four children.

“One day I was talking with one of the peshmerga commanders…who…quoted Napoleon Bonaparte, saying that ‘I am not afraid of 100 men with guns, but I am afraid of one man armed with a pen.’ Since then, I have always looked at my pen as my weapon. I consider myself a peshmerga, but I fight my battles with a pen.”

––from Chapter 4, A Student in the City

Sometimes they put innocent men in prison. This book is the story of one of those men.

Son of Mountains is a memoir by Yassin Aref, a UN refugee who sought peace and freedom for himself and his family in America––and found just the opposite. It is the story of a Muslim entrapped in a fictional “sting” concocted by the FBI, accused of aiding terrorism, and sentenced in 2007 to fifteen years in federal prison. And it is the story of an Iraqi Kurd––a “son of mountains”––who has struggled all his life just to survive.

Yassin Aref was born to illiterate farming parents in a village in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan in 1970. However, his was a famous family; his grandfather and uncle had been Muslim imams (religious leaders) loved and respected by thousands. Yassin grew up under the rule of Saddam Hussein, encountering tremendous poverty, brutality, and repression; as a teenager, Yassin sympathized with the Kurdish peshmerga (freedom fighters) and risked his life opposing the dictator’s genocide against the Kurds.

In 1995, Yassin married and made the wrenching decision to leave his beloved Kurdistan for Syria. Although he worked full-time to support his growing family, he managed to graduate from Abu Noor University in Damascus with a degree in Islamic studies. But Kurds had no freedom or rights in Syria, and in 1999 the stateless family was given refugee status by the UN and sent to Albany in upstate New York to begin a new life in America. An immigrant once more, Yassin worked at several low-paying, often temporary jobs until he was appointed imam of Masjid as-Salam (House of Peace), a small Albany mosque. The 2004 FBI raid on the mosque and Yassin’s arrest, which was nationally reported as a victory in the “war on terror,”and his trial and conviction in 2006, tore his family, the mosque, the community, and the city apart.

By the end of this extraordinary memoir, filled with the peaceful, practical morality of Islam as well as flashes of humor, the reader will understand why Yassin is no terrorist, and how grave an injustice has been done. The book ends with an outspoken essay by volunteer lawyer Stephen Downs that details how the government’s case against Yassin was not a “sting” but a simple frame-up––an elaborate fiction presented in court as fact––with lives, families, and Constitutional rights sacrificed to our post-9/11 climate of fear.

Here are excerpts from the book:

From Chapter 7, Kurdish Uprising:

It is almost impossible to describe the scenes of chaos and devastation. It was like the flood in New Orleans except that the planes flying overhead were shooting at us rather than trying to help, and we were climbing through wild mountains rather than struggling through a city. At one point we saw a woman in complete despair take her baby and throw it over a cliff. One of my friends climbed down the cliff to try and save the baby, but when he returned he said that it was dead.

Sometimes we carried children who could not keep up with their families. Sometimes we gave them food. Sometimes we tried to reassure people who were too frightened to think clearly. Sometimes we tried to give people directions. One day while we were climbing a mountain trail, we saw an old man who had been left behind. He called to us, “Son, son, please help.” I looked back at him, and I was shaken to see that he looked just like my sick father. It gave me such pain to think that I did not know whether he and my family had fled Bazyan, or anything at all about what was happening to them.

I stopped and went back to the old man, thinking about my dad, and my eyes filled with tears. I took his hand and started helping him climb the mountain trail.

“Thank you very much,” he told me,

“Thank God, not me,” I replied.

He looked at me strangely and said, “You’re a Mala (Imam)?”

“No, I am not.”

“No matter,” he said. “Just please explain to me, why is God punishing us?”

I said, “This, Saddam is doing for us––not God.”

“I know that Saddam is doing this,” he said. “I am talking about the rain. Does God not see all the women and children who have no shelter? Why doesn’t He stop the rain?”

“But it is not as cold as it usually is in the mountains,” I told him.

“You are right, but I was talking about the rain. Since we left our home it has not stopped raining.”

“My dad used to tell me all the time that rain is a blessing.”

“But not now. It is a punishment.”

“I don’t believe so,” I told him.

“What? You don’t see all these people under the rain day and night? Look at these women and children. Is this not punishment?”

“No. I believe this is protection for us.”

“How?” He looked at me in great surprise.“This weather prevented the government from using the air force against us. If it wasn’t for the rain, the helicopters would have picked us off one by one and then attacked the survivors.”

He just looked at me for awhile, thinking about what I had said. “Mala, I swear by God you are right. Never did I think about that. Just pray that it keeps on raining. God’s water is much better than Saddam’s fire.”

“God’s water drowns Saddam’s fire,” I said.

© 2008 by Yassin Aref. All rights reserved.

From Chapter 9, Breaking the Iron Wall:

A Kurdish student in Damascus did not speak much Arabic. He went to a store to buy tomatoes, but he wanted to make sure that he could select the tomatoes by touch. In Syria, sellers do not want you to touch the vegetables, so they will select them for you. But the student did not know how to say in Arabic that he wanted to select his own tomatoes. After awhile, he remembered the Arabic word for “voting” (tasweet), which he thought was similar to the Arabic word that means “choosing” (and can also mean “electing” or “election”––intikhab). So he asked the store owner, “Uncle, do you have voting for your tomatoes?”

And the owner said, “No. There is no democracy here for the vegetables.”

From Chapter 11, Politics:

One of the most famous Turkish writers and novelists, Aziz Nesin, said that if you are out in public, in a bus or a market or a tea shop, and someone asks you what time it is, do not answer. If the person tries to start a conversation about the weather, how hot or cold it is, don’t answer him. Say nothing––because all of this is just the first step to starting a dialogue with you. If you answer, the second step will be, What is your name? How are you? Where do you live? A formal introduction will follow. And if you take the second step, the third step will undoubtedly be political––and if you respond to the third step, you will certainly disappear. The wise man in the Middle East is the one who hides his watch, makes himself dumb, and closes his mouth to anything that leads to foolishness and trouble––and politics.

© 2008 by Yassin Aref. All rights reserved.

From Chapter 13, Welcome to the U.S.A.:

That Friday, I preached about the way we should deal with children, and I especially mentioned that not only was it OK to bring children to the masjid, they were even allowed to play as long as they behaved themselves when people were praying. I told them about how Mohammad, may peace be upon him, used to carry his grandsons Hasan and Hossain around, one on each shoulder. One day while the Prophet was prostrating himself in prayer, one of the grandsons came and jumped on his back. The Prophet stayed on the ground in prayer for a long, long time. After he finished praying, people asked him if something had changed in his prayers. “No,” the Prophet said. “But you lay prostrate for so long,” they said. “Oh,” he responded, “my grandson was on my back, and I wanted him to take his time.”

From Chapter 14, The Walls Can See and Hear:

In Iraq, you could not trust whether or not a stranger was an informant; in America, it is the same––even in the mosque you could not trust anyone because you did not know who was carrying a tape recorder. In Iraq they could jail you without evidence. In America, they jail you based on secret evidence they say is “classified.” In Iraq they told the Imams that they were not allowed to preach on certain topics. In America, they say that everyone is free to speak, but when you criticize the government you are accused of being anti-American and anti-Semitic. In Iraq there was no mail service and no international calls. In America there is mail and phone service, but the FBI will open your mail and wiretap your telephone. So feel free to write and say whatever you want, but be 100% sure that the FBI will read what you write, listen to what you say, and will arrest you if you are too truthful in criticizing the government. In Iraq they search your house right in front of you without a court order, but in America they break into your house after you have left for the day. The parallels between civil liberties in Iraq and America go on and on.

© 2008 by Yassin Aref. All rights reserved.

From Chapter 15, Jail Stories:

One day I was lying on my bed reading a book, which I usually do when there is nothing else to do. Sometimes I go deep into my book and forget the time, and even where I am. I vaguely heard the unit officer making his hourly check of the cells. I was so absorbed in my book that I had not paid attention to how many checks he had made, but this time as he passed I heard someone say, “Shako Mako” (Iraqi Arabic for “Hey, what’s new?”)…

I could not figure out who had greeted me, so I went back to my bed and began reading again. But “Shako Mako” kept running through my mind. The answer to this casual greeting…is usually “Nothing,” and so I answered Nothing a number of times in my mind. In jail, the answer is really true. Nothing is new: the same room, the same program, the same bed, the same sink, the same blanket, the same light, the same food. Nothing new goes on at all. When inmates explain what jail is like, they say, “Different day, same everything else.” And after awhile, we can say, “Different year, same everything else.” But my mind kept ringing with those words.

For the last fifteen years I had not heard “Shako Mako” spoken to me. It reminded me of my army friend, Raid, who taught me the phrase when I was ten years old, and he was the first person to whom I ever said it in return. Shako Mako: on my bed I was holding my book and pretending to read it, but I really did not comprehend any of the words on the page because I was back in Iraq, talking to Raid.

Then suddenly I heard it again, right outside my door: “Shako Mako.” I ran to my door window and I saw the same unit officer. Now I knew that it must be him, but how did he know these words?

When noon came and he brought my lunch, I asked him. He said that he had been in Iraq in the military for a year, and he had learned a few Arabic words. A few days later, he took us out for our one-hour break in the backyard, and I asked him about Iraq and what he had seen. He said he did not want to talk about it, but that it was terrible.

I said, “It is a different planet, no?”

And he said, “Exactly.” He was deeply troubled about the way people were forced to live, especially the children. He said it really bothered him, and it was hard for him to forget what he had seen. “It has even affected my life now,” he said. “It has made me a different person. I have trouble controlling myself. I get mad very easily, often for no reason.”

And I said, “You were just there for one year. What about the people who live there?”

After that, I saw him many times, and he occasionally said two or three Arabic words to me with an Iraqi accent. One day when I went to get some hot water for tea, he said, “O-guf! Tera armeek.” I stood up immediately, and he laughed and came over to me. “What does that mean?” he asked.

“Repeat it,” I said.

“O-guf! Tera armeek,” he said, and after he repeated it a few more times I understood.

“It means, ‘Stop. Don’t move or I will shoot,’” I said.

He seemed pleased that I had figured out exactly what he wanted to say.

“How many people did you shoot there?” I asked him.

He refused to tell me. I took my hot water and went back to my cell, but I really felt sad. I thought, How many innocent Iraqis may have been shot because they could not understand what he was saying? I myself had not understood him until he had repeated it two or three times, and if I had been in Iraq it could have cost me my life. I thanked God that I was not in Iraq, and that I had not met the guard with a loaded gun in his hands.

© 2008 by Yassin Aref. All rights reserved.

For an excerpt from Profile of a Frame-Up, click here.

After the verdict, I watched Terry Kindlon interview new clients. I understood that he had to take new cases to keep his practice going; I had done the same in my career. But this time I found that I could not move on. I had never before in my professional life encountered a deliberate frame-up. I was familiar with prosecutorial abuses that led to innocent men being convicted––sloppy police work, concealment of errors, hubris and arrogance––but what happened to Yassin was something quite different. The government had deliberately plotted to convict a man who they knew had not committed a crime. There was no sloppiness, no incompetence, but rather a cold, calculating plan carried out over a long period of time, costing millions of dollars and involving dozens of agents, prosecutors, and the acquiescence of high-level officials, to convict two men of terrorism who had no involvement or interest in terrorism. This frame-up was a basic shift in my experience as a lawyer. I had practiced law for over thirty-five years with certain assumptions about the rights of individuals and the limitations of government, but I could not adapt my assumptions to this new reality. For me, Yassin’s case would not be over until the injustice was corrected. Besides, he was now my brother.

© 2008 by Stephen Downs. All rights reserved.

Updated

October 29, 2009

This site is maintained by Lynne Jackson of Jackson's Computer Services |